What's New

Mythic Living

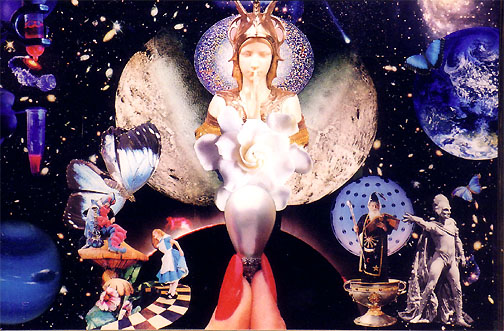

About Pantheon

Archetypes

Divination

Ritual

Personification

Child

Body & Soul

Persephone

Gowan

Attractors

Eulogy

RITUAL

Neurology, Ritual, and Religion:

An Initial Exploration

Cliff Guthrie, Copyright 2000

http://www.geocities.com/iona_m/Neurotheology/Neuroritual.html

Myth Resolution Through Ritual

Within the brain, the autonomic nervous system regulates and adjusts baseline body function and responds to external stimuli. It consists of two mutually inhibitory subsystems: the sympathetic or arousal system and the parasympathetic or quiescent system. The arousal system is the source of our fight or flight response, and is connected to the adrenal glands, the amygdala, and reaches into our left cerebral hemisphere. It is sometimes called the "ergotropic" system because it releases energy in the body to react to the environment.

The parasympathetic or quiescent system (sometimes called the "trophotropic" system), on the other hand, conserves energy, promotes relaxation and sleep, and maintains basic body function and growth. It includes the endocrine glands, parts of the hypothalamus and the thalamus, and reaches into the right cerebral hemisphere. Although this material is highly complicated, the most important relationships to keep in mind here is that the dominant (analytical) mind is connected to the arousal system and involves the amygdala, and the non-dominant (holistic) mind is connected with the quiescent system and involves the hypothalamus and hippocampus.28

D’Aquili and Laughlin report research that shows that when either the arousal or quiescent system is maximally stimulated it results in a "spillover effect" or a stimulation of the other system. That is, experts in meditation may experience a "rush" or a release of energy during a hyperquiescent state. From the other side, those who engage in rhythmic rituals that engage the arousal system, such as energetic dancing and singing, may experience states of bliss, tranquility, and oneness with others.29

Hyperarousal and hyperquiescent states seem to stimulate the limbic system, which regulates our emotions. Hence, these states are experienced as being emotionally intense, and often pleasurable.

It is also during these "spillover" experiences that the paradoxes presented to the brain through myth become resolved by the simultaneous functioning of both hemispheres of the brain. In ritual stimulation of the arousal system, for example, the presentation of what is an unresolvable logical problem in the left brain (the wafer is both bread and the Body of Christ), is experienced as unified in the holistic operation of the right brain.

Ritual participants therefore may experience a resolution of the problems presented by the myth and a deep unity with other participants: "The simultaneous strong discharge of both parts of the autonomic nervous system creates a state that consists not only of a pleasurable sensation, but, also, under proper conditions, a sense of union with conspecifics and a blurring of cognitive boundaries."30 Similarly, those who engage in meditation may report that they experience resolution of paradoxes during some meditative states, hence the famous use of such paradoxes by Zen practitioners.

Both meditation and ritual can lead to the spillover effect and the simultaneous discharge of the arousal and quiescent systems. But they come at the experience from different directions. Meditation begins with the quiescent system and by its hyperactiviation can achieve spillover into the arousal system (from trophotropic to ergotropic). Ritual approaches from the opposite system (from ergotropic to trophotropic). But there are other differences as well:

The difference between meditation and ritual is that those who are adept at meditation are often able to maintain an ecstatic state for prolonged periods of time. The ecstatic state and sense of union produced by ritual are usually very brief (often lasting only a few seconds) and may often be described as no more than a shiver running down the back at a certain point.

This experience, however, may be repeated at numerous focal points during the ritual. Furthermore, the ecstatic states produced by ritual, although they are usually extremely brief, seem to be available to many or most participants. The ecstatic states attained through meditation, although they may last for hours or even days, require long practice and intense discipline.31

So ritual is more accessible and effective than meditation for large groups of people as a system for stimulating both hemispheres of the brain and thereby bringing mythic conundrums to resolution. In The Mystical Mind, d’Aquili and Newberg elaborate on the difference between these approaches, describing a complex continuum of unitary or mystical states that may arise from different types ritual or meditation, but the basic principles remain intact.

Ritual is here described as a "bottom-up" technology for activating the autonomic systems; its rhythmic qualities stimulate either the arousal or quiescent systems that then affect the higher brain functions. Slow rhythms in ritual, like chant and read liturgy, primarily stimulate the quiescent system, while rapid "driving" rituals involving loud noise and body movement stimulate the arousal system. Either approach may lead to a "filling up" of the autonomic system and then a spillover effect and an altered state of consciousness.

Slow ritual may lead to a hyperquiescent state and a feeling of peace or unity, and occasionally result in a spillover into the arousal state or a sense of profound energy. Similarly, fast ritual may provoke a hyperarousal state of attention and intention, sometimes spilling over into the quiescent state and a sense of bliss. They hypothesize that ritual could theoretically lead to the maximal discharge of both systems, causing hallucinations, mystical visions, or a state of Absolute Unitary Being (AUB).

Finally, they note that marked ritual behavior tends to draw the attention of the amygdala, as does strong smell, which may be the biological source of the experience of religious awe. Ritual actions and the presence of incense may help neurologically for ritual to promote altered states of consciousness in its participants.32

In summary, according to biogenetic structural analysis, humans do ritual for the same reasons other animals do them: to diminish distance between other members of the species, to coordinate group action, socialize their young, and communicate status and social structure. What is unique about human ritualizing is its connection to the human propensity to create myths.

Myths themselves contain logical or story resolutions to the paradoxes of our lives, but do not solve the problem existentially because they remain only as logical or left-brain solutions. As Austin Farrer used to insist, we cannot believe very long in a God with whom we have nothing to do; faith, he wrote, "cannot be got going by stoking up the furnaces of the will."33 So ritual does give us something specific to do.

In our attempt to address the unknown causes of the phenomena that affect their lives, we engage in rituals that stimulate brain states that bring convincing, felt, and physical resolutions to our dilemmas. Some theorists have puzzled over why religion continues to hold so much power for postmodern people, expecting that we would have learned by now that we cannot control the gods or forces of nature through ritual behavior.

D’Aquili and other biogenetic structuralists have countered that ritual, in fact, does work effectively for us because it brings mythical paradoxes and unsolved problems to resolution through excitation of neurological processes by motor activity. The myths become experienced fact. Because such a resolution promotes a sense of unity with others and is a pleasurable experience, it is highly adaptive for humans who are trying to make their way in the world.

Ritual behavior is one of the few mechanisms at [our] disposal that can possibly solve the ultimate problems and paradoxes of human existence. Thus, although ritual behavior does not always "work," it has such a powerful effect when it does work that it is unlikely ever to pass out of existence within a social context, no matter what the degree of sophistication of society.

Religious ritual behavior may take new forms within the context of highly developed Western technological societies. But whether in new form or in old, it is much too important to the psychological well-being of a society to lapse into oblivion.34

After their account of the neurophysiology of ritual, d’Aquili and Newberg include short sections in The Mystical Mind called "Improving Ritual and Liturgy" and "Future Liturgy" in which they begin to apply their theory to liturgical practice. Their comments are specifically directed to Western culture, particularly Christianity and Judaism. First, they insist that, "In order for liturgy to work effectively, it must carry many rhythmic components."

They suggest that it is appropriate for liturgy to adapt its rhythmic elements to speak to the particular theme of a specific liturgical event (Easter, baptism, Rosh Hashanah), and to carry rhythmic elements that refer to the basic myths of the religion in which the particular liturgy is a part. They also add, "The arrangement of various religious rituals as well as the tenets of a given religion must be set in a rhythm between permanence and impermanence." By this they seem to mean simply that the ritual rhythms of liturgy must both reflect its ancient mythic roots and speak appropriately to the local culture.

Finally, they suggest that the rhythm of any given ritual element should try to match the mythic effect of the story being told. A slow rhythm or chant that stimulates experiences of peace would be appropriate for a text that suggests the love of God. "In the end," they write:

a liturgical sequence that employs both aspects of arousal and of quiescence—some rapid songs, some slow hymns; some words of love, some words of fear; stories of glory, stories with morals; prayers exalting God and prayers asking for help—will allow for the participants to experience religion in the most powerful way. They will experience the profound peace of the love of God, fear and awe of the power of God, and a strong sense of what is right and moral.

If a ritual has just the right rhythms, however, then the participants may briefly experience something a step further. If the arousal and quiescent systems are activated during ritual, then they may experience a brief breakdown of the self-other dichotomy. This breakdown will be interpreted within the theology and stories of the religion, and this powerful experience will give the participants a sense of unity with each other because they are all taking part in the same ritual.

Furthermore, the participants may have a sense of being more intensely united to God or to whatever the religious object of prayer or sacrifice may be. This liturgical sense of unity can allow everyone (not just monks or mystics) a chance at moving across the unitary continuum to experience the mystical—a sense of unity with God, with the universe, or with whatever is "ultimate."35

To the question of whether such knowledge may lead future ritualists to be able to better manipulate their ritual participants, d’Aquili and Newberg counter that liturgists have long been aware of techniques of marrying rhythm and meaning. It would seem to me that all ritual is manipulative in the sense that it seeks to wed rhythm with story to stimulate certain emotional responses.

What their theory may clarify, however, is why some people who are accustomed to associating their religious myths with a slow rhythmic ritual and the stimulation of their quiescent system would find it so difficult to enter a ritual that married the same myth to a fast rhythmic ritual that stimulated the arousal system.

Can the quiescent God of formal "high" liturgy, for example, ever be quite at home with the aroused God of some contemporary or charismatic worship?

There is further need for discussion of the objections to or applications of this biogenetic structuralist account of ritual that the limits of this paper cannot pursue. For now I’ll turn to describe briefly one researcher whose account of the neurological basis of religious experience has gained some attention.

What's New with My Subject?

If I didn't include a news section about my site's topic on my home page, then I could include it here.